Weathering the Storm: Why Staying Invested Matters More Than Ever

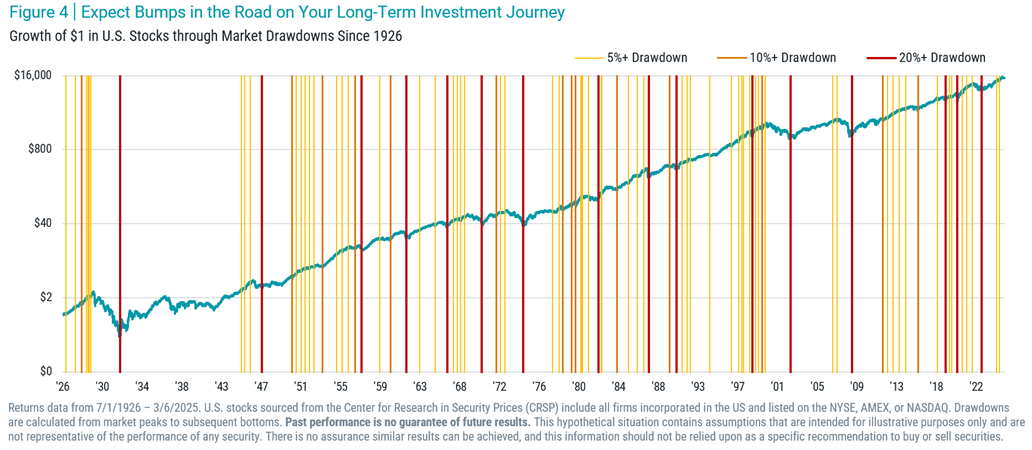

In light of the recent market volatility triggered by newly announced tariffs, it’s natural to feel uneasy. Market pullbacks like the one we’re experiencing can stir up fears and tempt us to retreat to the sidelines. But history reminds us: some of the strongest investment gains come after the storm.

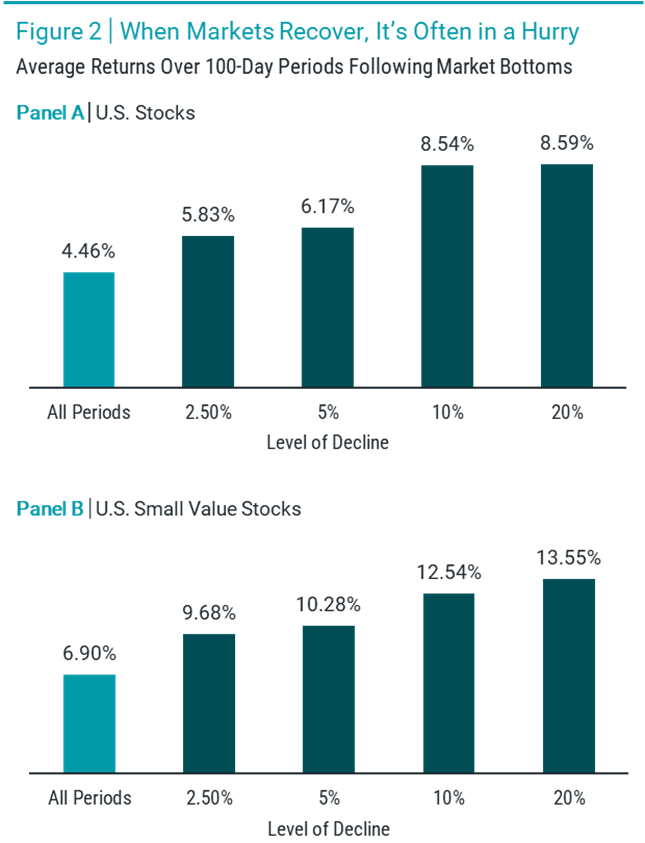

As shown in the chart below, markets often rebound quickly after significant declines. In fact, after a 10% or greater drop, U.S. stocks have returned over 8.5% on average in just the next 100 days. For small-value stocks, that rebound has been even stronger. This illustrates a powerful point: missing the recovery can really hurt.

Trying to time the market means risking being out during those crucial early days of recovery. And with uncertainty around tariffs and global trade, that rebound could come quickly and unexpectedly.

Now is the time to stay focused on long-term goals, not short-term noise.

Data from 7/1/1926 – 2/28/2025. U.S. stocks sourced from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) include all firms incorporated in the US and listed on the NYSE, AMEX, or NASDAQ. Source: Avantis Investors. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This quarter’s newsletter is designed to help educate and make sense of the recent volatility in markets, particularly through the lens of tariffs and industrial policy. While these shifts can feel disruptive, they often lay the groundwork for future growth. Our goal is to provide clarity around what’s driving the turbulence and where the opportunities may emerge as the landscape settles.

Tariffs: A Two-Edged Sword for Manufacturing and Revenue

April 2025 Policy Context: The Trump administration’s recent April 2 announcement of sweeping new tariffs – including reciprocal duties on many imports and a 25% tariff on all foreign-made vehicles – has rekindled debate about tariffs as an economic tool. Leaving Investors asking:

Can tariffs simultaneously protect domestic manufacturing and raise substantial government revenue?

History and data suggest that these dual goals are inherently at odds. In this newsletter segment, we examine the limitations of tariffs as a dual-policy tool, drawing on U.S. and global examples, economic research, and the long-term implications for investors.

Protection vs. Revenue: An Inherent Conflict

Tariffs have a dual nature. They are taxes on imports aimed at making foreign goods more expensive, thereby encouraging consumers to buy domestic alternatives. This can shield domestic industries from foreign competition. Tariffs also generate government revenue from import duties. However, these goals often conflict. If tariffs succeed in dramatically reducing imports to protect home industries, there is less imported volume to tax – meaning less tariff revenue. Conversely, if tariffs are kept low enough that imports continue robustly, they offer little protective effect for domestic producers.

Historical U.S. policy recognizes this tension. In the 19th century, when tariffs were the U.S. government’s main revenue source, policymakers set moderate tariffs to avoid choking off imports entirely. Keeping tariffs low can maintain import levels and revenue but results in little protection for domestic firms. This trade-off is essentially an economic curve beyond a point, higher tariff rates shrink the tax base so much that total revenue falls.

Modern data: Even after the tariff hikes of 2018–2019, U.S. customs duties remain a drop in the bucket of federal finances. Tariff receipts were about $77 billion in FY2024 – roughly 1.5% of the $5.27 trillion in total federal revenue. This is despite average U.S. tariff rates roughly doubling from 1.4% in 2017 to ~2.8% by 2020 due to the Trump-era measures. The small revenue share underscores that tariffs alone cannot meaningfully fund government operations or debt reduction without extraordinarily high import taxes – which would themselves crimp trade volumes.

Lessons from Tariff History: Limited Manufacturing Gains

History provides instructive examples of tariffs intended to revive or protect industries:

- Smoot–Hawley Tariff (U.S., 1930): A sweeping tariff hike averaging ~20% on thousands of goods, enacted to shield American farms and factories during the Great Depression. The result was disastrous. U.S. trading partners retaliated in kind; world trade collapsed by an estimated 66% between 1929 and 1934, exacerbating the global downturn. U.S. manufacturing did not enjoy a recovery; instead, the high tariffs deepened the economic slump and cut off markets for U.S. exporters. Tariff revenues also dried up as imports became unaffordable or unavailable.[i]

- Steel Tariffs (U.S., 2002): President George W. Bush imposed temporary tariffs (up to 30%) on steel imports to protect the domestic steel industry. Studies later found the tariffs failed to boost U.S. steel employment – but they substantially depressed employment in steel-using manufacturing sectors (e.g. auto parts, machinery) that faced higher input costs. One estimate is that steel-consuming industries lost many more jobs than the total workforce of the steel industry, due to higher steel prices making downstream products less competitive. These tariffs were withdrawn after about 18 months in the face of WTO challenges and economic costs.[ii]

- Tire Tariffs (U.S., 2009): In 2009, the U.S. imposed a 35% tariff on Chinese automobile tires to protect domestic manufacturers. While this policy saved an estimated 1,200 American tire manufacturing jobs, it came at a significant cost. U.S. consumers paid approximately $1.1 billion more for tires in 2011 due to higher prices, equating to over $900,000 per job saved. Most of this cost benefited tire companies, both domestic and foreign, rather than the workers. Additionally, higher tire prices acted like a tax on consumers, potentially reducing spending in other areas and affecting retail sector employment. This case highlights that protectionist tariffs can have widespread costs that may outweigh the concentrated benefits to a small group of workers.[iii]

- “Trade War” Tariffs (U.S., 2018–2019): The Trump administration implemented tariffs on steel (25%), aluminum (10%), and over $300 billion worth of Chinese goods (10–25%) with the aim of revitalizing U.S. manufacturing and reducing the trade deficit. While certain protected industries experienced short-term gains, the broader manufacturing sector did not see a significant resurgence.[iv]A study by the Federal Reserve found that these tariffs resulted in a net loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs. Specifically, any job gains from import protection were more than offset by job losses due to higher input costs and retaliatory tariffs affecting U.S. exports.

Additionally, the overall U.S. trade deficit in goods did not show a significant improvement. While imports from China decreased, they were largely replaced by imports from other countries, effectively reshuffling the trade gap rather than eliminating it.

An analysis by Oxford Economics estimated that the trade war tariffs, along with retaliation effects, cost the U.S. economy approximately 245,000 jobs and 0.5% of GDP by 2020, while also increasing consumer costs. [v]

- Protection in Other Major Economies: The United States is not alone in deploying tariffs to nurture industries, though major economies today use them selectively.

- China maintained high tariffs and import restrictions through the 1990s to support domestic manufacturing. Tariffs on autos and electronics, often 25% or more, encouraged foreign firms to produce locally through joint ventures, helping build China’s industrial base. While this strategy supported growth, it came at the cost of higher prices for Chinese consumers and friction with trade partners. Many of these barriers were scaled back after China joined the WTO in 2001 and integrated more fully into global supply chains.

- Japan and South Korea in the postwar era similarly used tariffs and quotas in targeted industries (like Japan’s barriers against U.S. autos in the 1980s) alongside industrial subsidies – a strategy that fueled domestic champions but often at the cost of trade friction.

- The European Union today applies a common external tariff (for instance, a ~10% tariff on imported cars from non-EU countries) aimed at protecting EU automakers. While EU auto tariffs encouraged foreign firms to establish plants inside Europe (providing jobs locally), European consumers have historically faced higher car prices as a result.

Tariffs can help grow domestic industries, but they often raise consumer costs and strain trade relationships. When tariffs fully block imports, like the 25% U.S. light truck tariff, domestic firms face no competition, but the government collects little revenue. In effect, protection often comes at the cost of both trade and tax receipts.[vi]

Data Snapshot: Table – Selected Tariff Interventions and Outcomes

| Tariff Policy (Year) | Stated Goal | Outcome |

| Smoot–Hawley Act (1930, US) – broad 20% average tariff hike on 20k+ goods | Protect U.S. farms & factories; raise revenue in Depression | U.S. trading partners retaliated; world trade fell ~66%. Deepened Great Depression; minimal benefit to U.S. industry. Tariff revenue fell amid collapsing imports. |

| Steel Tariffs (2002, US) – up to 30% duties (Section 201 safeguards) | Save steel mills & jobs in US steel industry | No increase in steel employment; employment in steel-using industries fell due to higher input costs. Tariffs lifted early to avoid broader harm. |

| Tire Tariffs (2009, US) – 35% duty on imported Chinese tires | Protect U.S. tire manufacturing jobs | Saved ~1,200 jobs but at $900k+ cost per job (>$1 billion in higher prices). Loss of ~3,700 retail jobs as consumers spent more on tires, less elsewhere. |

| “Trade War” Tariffs (2018–19, US) – 10–25% on steel, aluminum, and $370B of imports (China & others) | Boost U.S. manufacturing; reduce trade deficit; punish China | U.S. manufacturing jobs net ↓1.4% vs. no tariffs. Trade deficit reallocated (no big overall drop). Tariff revenue ~doubled to $80B, but U.S. firms and consumers bore higher costs. Some U.S. export industries hit by retaliation. |

| Auto Tariffs (ongoing, China & EU) – e.g. China’s ~25% (now 15%) auto tariff; EU ~10% on cars | Develop/retain domestic auto production capabilities | Foreign automakers built local factories to bypass tariffs (jobs created locally). Consumers in importing country faced higher prices. Government revenue limited as imports diverted or produced locally. |

(Sources: USITC, Peterson Institute, Brookings, WTO, news reports as cited in text.)

Why Tariff Revenue and Import Replacement Conflict

The above cases illustrate why raising significant tariff revenue while also revitalizing domestic production is a balancing act that often fails. When tariffs are used to aggressively curb imports, they can indeed prompt some domestic production to fill the gap – but then fewer imports remain to tax, capping revenue. For example, if a 25% tariff on a product causes import volumes to drop by half, the government might collect more revenue per unit but from far fewer units, possibly even reducing total tax take.

In extreme cases like Smoot–Hawley, import volumes collapsed so much that tariff receipts actually declined despite higher rates (as happened in the early 1930s). On the other hand, a modest tariff that doesn’t significantly deter imports offers little relief to domestic producers, who still face foreign competition. This built-in contradiction limits tariffs’ usefulness as a dual policy lever.

The Trump administration’s tariffs demonstrate this tension. U.S. tariff revenue roughly doubled under the 2018–2019 measures, reaching an $80 billion annual rate by late 2019. But this was still a small fiscal contribution and came only because imports continued, albeit at somewhat lower levels. Had the tariffs been even higher or truly prohibitive, importers would have sourced elsewhere or not at all, and revenue gains would have evaporated.[vii]

In fact, import volumes of affected goods did fall (e.g. imports from China dropped sharply, some supply chains relocated) indicating that a portion of the intended import substitution happened, but not enough to annihilate the tax base.

The optimal tariff for revenue is usually a moderate rate: high enough to generate tax per unit, but not so high as to kill off imports entirely.

Policymakers thus face a trade-off: tariffs can be either mostly symbolic (low and revenue-generating) or disruptive (high and protective) but doing both effectively is extremely difficult.

Who Really Pays a Tariff? Limited Foreign Absorption

A key economic question for tariffs is who bears the cost – the foreign exporter or the domestic importer/consumer? The answer affects how effective tariffs are at either goal:

- In rare cases, foreign producers may absorb a tariff by cutting prices, softening the impact on U.S. consumers while still generating revenue. This tends to happen only when the exporter has pricing power—like a monopoly—and a strong reason to stay in the U.S. market. But outside of those scenarios, the cost of tariffs usually falls on American businesses and consumers.[viii]

- When U.S. importers and consumers bear the cost, tariffs act like a domestic tax—raising prices, slowing demand, and pressuring margins. While imports become less competitive, the burden falls on American businesses and households, not foreign producers.

In practice, most of the data shows that U.S. importers and consumers end up shouldering the cost of tariffs. During the 2018–2019 period, several studies found little evidence that foreign exporters lowered their prices in response. A joint study by Princeton, Columbia, and the NY Fed found nearly full pass-through, meaning the tariffs were almost entirely reflected in higher prices for American buyers.

The Tax Foundation also noted that while there have been some cases historically where foreign firms shared part of the cost, recent tariffs were largely paid by U.S. businesses and consumers. Even across different product categories, the pattern was consistent: Americans bore the full burden.

There was one partial exception with steel. Exporters from the EU, Japan, and South Korea initially passed on the full tariff, but later reduced their prices by 4–5% to stay competitive. That kind of adjustment only really happens when suppliers have pricing power and strong incentives to hold market share. But even then, U.S. buyers still paid more than before.[ix]

The bottom line: tariffs mostly act as a tax on U.S. consumers. Foreign suppliers rarely eat the cost—unless they have monopoly-like pricing power or are desperate to hold on to the U.S. market. So, while it’s sometimes claimed that “foreigners pay the tariff,” that’s rarely the case in practice.

And even when they do lower their prices, there’s a catch—the government collects less revenue, since tariffs are based on the price of the good. So, if the price drops, so does the tariff income. That trade-off underscores the broader point: tariffs can offer protection or revenue, but doing both well at the same time is tough to pull off.

Why Did the U.S. Industrial Base Decline?

For clients concerned about reviving domestic manufacturing, it’s important to understand the long-run forces at work. The U.S. industrial base has eroded over decades due to a combination of factors, not just trade policy:

- Productivity & Automation – S. manufacturing output has nearly doubled since the late 1970s, but with far fewer workers. Employment peaked at 19.6 million in 1979 and fell to 12.8 million by 2019, a 35% drop, while productivity surged. This shift reflects automation, leaner processes, and a broader move toward services. [x]

- Globalization & Offshoring – From the late 1990s, companies moved labor-intensive production overseas to cut costs. China’s WTO entry in 2001 accelerated this trend, especially in sectors like apparel and electronics. While consumers benefited from lower prices, many U.S. factory jobs disappeared, particularly in the Rust Belt. [xi]

- Policy & Investment Choices – Unlike some countries, the U.S. historically offered limited industrial subsidies and underinvested in manufacturing infrastructure and workforce training. Meanwhile, countries like South Korea and Taiwan used coordinated policies to build globally competitive industries. [xii]

- Strong Dollar & Structural Trade Gaps – The U.S. dollar’s strength makes exports pricier and imports cheaper, contributing to trade deficits.

Given this context, tariffs are a blunt instrument to rebuild an industrial base that has been shaped by 40+ years of technology and globalization. Ha-Joon Chang, a development economist, points out that the U.S. industrial base has been “run down… over four decades. It cannot be built up in two years or whatever tariff policies you have.” [xiii]

Reversing such long-term trends would require sustained structural efforts well beyond a short-term tariff hike.

Rebuilding Manufacturing: A Long-Term Project

If the policy goal is to restore domestic manufacturing capacity, tariffs may be one piece of the puzzle, but they are far from sufficient and work only with a long-time horizon:

- Time and consistency: Building or expanding factories is a multi-year (often decade-long) process. Companies need confidence that a protective tariff regime will last; otherwise they risk investing in facilities that could become unprofitable if tariffs are removed. Uncertainty around trade policy (e.g. tariffs imposed and lifted unpredictably) can deter investment in new U.S. production. [xiv]

- Infrastructure and supply chain ecosystem: Reviving an industry isn’t just about one factory; it requires recreating supplier networks and support infrastructure. For example, if the U.S. wants to produce all its own electronics, it would need not just assembly plants, but also domestic suppliers for components (chips, batteries, displays), raw materials processing, specialized equipment, and so on. Many of these upstream activities left the U.S. years ago. Rebuilding them may require parallel investments and coordination. Similarly, industries like automotive or aerospace rely on a web of parts suppliers. Tariffs can encourage final assembly onshore, but if critical components still must be imported (and face tariffs), domestic producers could remain at a cost disadvantage. [xv]

- Workforce skills: A skilled workforce is crucial. Decades of manufacturing decline mean fewer Americans with relevant trade skills. If a tariff suddenly makes it profitable to open a factory, will there be enough qualified workers to staff it? As Ha-Joon Chang emphasizes, “you need workers with the right skills… You even need universities around to do research” supporting the industry. Rebuilding the talent pipeline can take a generation. Many advanced manufacturing roles today also require higher technical literacy due to automation, which was highlighted in an interview with Apple’s Tim Cook. [xvi]

- Capital and innovation: Modern manufacturing is capital-heavy. Reshoring production requires major investment in automation, robotics, and high-end equipment—just to stay globally competitive. Tariffs alone aren’t enough. That’s why recent efforts, like the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act, include direct subsidies and tax incentives to attract long-term investment. Still, success isn’t guaranteed if U.S. production costs stay well above global norms. In sectors like advanced semiconductors, rebuilding capacity will take years and tens of billions—and even then, the results remain uncertain.

In summary, tariffs can provide a temporary shield, but rebuilding a robust industrial base is a long-term endeavor requiring structural investment in people, capital, and supply chain networks. During the adjustment period, the economy may face higher costs and inefficiencies. Policymakers and the public would need to tolerate these in hope of eventual payoffs.

This balance between short-term pain and long-term gain is delicate, and political support can waver if the promised manufacturing revival does not materialize quickly.

Stagflation an Emerging Risk: Tariff-Induced Supply Shocks

We have been asked on the stagflation scenario, below is for education and context, not a prediction this is where we are heading. The greatest risk of stagflation today stems from persistent supply-side shocks like tariffs, reshoring costs, and labor shortages occurring alongside tight monetary policy. This unusual combination leads to rising costs and slowing growth or outright stagnation. If not addressed with care, it creates a self-reinforcing economic trap.

Why Stagflation Is Dangerous

- Traditional policy tools don’t work well: Raising rates curbs inflation—but slows growth further. Stimulus boosts demand—but risks even more inflation.

- Erodes real income: Prices rise faster than wages, squeezing households.

- Hurts both workers and investors: Companies face declining margins while consumers cut back. This pressures earnings, spending, and asset valuations at once.

- Uncertainty stifles investment: Businesses hold off expansion or hiring amid volatile costs and weak demand.

Escaping stagflation requires targeted action:

- Supply-side fixes: Reduce tariffs and trade friction, improve logistics, expand skilled labor programs, and incentivize productivity-boosting investment.

- Credible inflation control: Central banks must maintain inflation-fighting credibility to anchor expectations—without over-tightening.

- Structural reforms: Encourage competition, energy access, and capital formation to unblock economic bottlenecks.

- Policy coordination: Monetary and fiscal authorities must avoid working at cross purposes—tightening in one direction while stimulating in another.

Stagflation is rare but painful, difficult to fix without short-term costs. Today’s policy choices, especially around tariffs and supply chains, could influence whether the U.S. tiptoes into it or avoids it altogether.

The U.S. experiences higher inflation (from tariffs and reshoring inefficiencies) while GDP slows or contracts, creating a stagflation-like environment, reminiscent of the 1970s, but rooted in geopolitics and trade fragmentation rather than oil shocks.

Our viewpoint and what to do…

This quarter’s newsletter was meant to provide an educational lens into the economic mechanics behind the recent rise in market volatility, particularly around tariffs and industrial policy. These types of policy shifts, while disruptive in the short term, often become embedded in the long-term growth narrative.

The use of tariffs to simultaneously support domestic manufacturing and generate revenue is not without trade-offs. History and data show that, on their own, tariffs have limited capacity to rebuild industry, especially without broader investments in labor, infrastructure, and innovation. They can raise costs for consumers and businesses alike and may trigger global responses that add to market complexity.

That said, we believe these current dislocations are part of a longer arc. Over time, supply chains will adjust, new sectors will emerge, and policy clarity will return. These shocks are real, but not permanent and the path back to stability is within reach, hinging on a handful of thoughtful decisions from global leadership.

As always, our focus is on helping you stay ahead of the curve. We continue to monitor these dynamics closely and position portfolios to navigate volatility while staying anchored to long-term opportunity.

Sources and Endnotes:

- U.S. Trade Representative and news releases on April 2025 tariff actions

- Historical tariff impacts and policy context: Cato Institute analysis; Council on Foreign Relations; Peterson Institute for International Economics

- U.S. manufacturing employment and output data: Federal Reserve, BLS (Econofact); Bureau of Labor Statistics reports

- Case studies: PIIE on 2009 tire tariffs; AEA Journal on 2002 steel tariffs; Brookings and Tax Foundation on 2018–19 tariffs; WTO and OECD reports

- Tariff incidence research: University of Chicago Q&A; Tax Foundation summary of tariff studies; Federal Reserve and NBER working papers

- Expert commentary on industrial base rebuilding: PBS interview (Ha-Joon Chang); Brookings Institution and CSIS analyses on deindustrialization and industrial policy.

Disclosure:

LA Wealth Advisors is a dba of Axxcess Wealth Management LLC, a registered investment advisor. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Axxcess and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure

The information provided is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. It does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status or investment horizon. You should consult your attorney or tax advisor.

The views expressed in this commentary are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur.

All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. There is no representation or warranty as to the current accuracy, reliability or completeness of, nor liability for, decisions based on such information, and it should not be relied on as such.

[i] https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/protectionism#:~:text=Milestones%3A%201921%E2%80%931936%3A%20Protectionism%20in%20the,20th%20century%20American%20trade%20policy

[ii] https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/265944

[iii] https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/2016/us-tire-tariffs-saving-few-jobs-high-cost

[iv] https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/disentangling-the-effects-of-the-2018-2019-tariffs-on-a-globally-connected-us-manufacturing-sector.htm

[v] https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/case-study/modelling-the-costs-of-us-china-tariffs/

[vi] https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/the-anti-consumer-25-chicken-tax-on-imported-trucks-has-insulated-the-big-3-from-foreign-competition-for-50-years/

[vii] https://wolfstreet.com/2025/02/03/what-trumps-tariffs-did-last-time-2018-2019-had-no-impact-on-inflation-doubled-receipts-from-customs-duties-and-hit-stocks/

[viii] https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_international-trade-theory-and-policy/s12-06-the-case-of-a-foreign-monopoly

[ix] https://taxfoundation.org/blog/who-pays-tariffs/

[x] https://www.csis.org/analysis/do-not-blame-trade-decline-manufacturing-jobs#:~:text=38%20percent%20during%20World%20War,of%20imports%20and%20exports%20were

[xi] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2024/10/15/the-globalization-and-offshoring-of-us-jobs-have-hit-americans-hard/

[xii] https://www.epi.org/publication/botched-policy-responses-to-globalization/

[xiii] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/examining-trumps-claims-that-tariffs-will-revitalize-american-manufacturing#:~:text=%2A%20Ha

[xiv] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/examining-trumps-claims-that-tariffs-will-revitalize-american-manufacturing#:~:text=%2A%20Ha

[xv] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/examining-trumps-claims-that-tariffs-will-revitalize-american-manufacturing#:~:text=%2A%20Ha

[xvi] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L9f5SQQKr5o&feature=youtu.be

LA Wealth Advisors is a DBA of Axxcess Wealth Management, LLC a Registered Investment Advisor with the SEC. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Axxcess and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure.

All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. There is no representation or warranty as to the current accuracy, reliability or completeness of, nor liability for, decisions based on such information, and it should not be relied on as such.

The information provided is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. It does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status or investment horizon. You should consult your attorney or tax advisor.

The views expressed in this commentary are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur.